Last month students in Professor Pete Patnode’s Criminal Investigations (CRJ 142) class began a conversation with him about what their final exam would look like. They didn’t want to do a lengthy paper, and he was opposed to a multiple choice test. The students decided they wanted the opportunity to show what they had learned by going through a mock crime scene exercise, and Patnode agreed. “I love hands-on learning. It’s the best way to measure what a student retains, what they can use, and how they can retrieve it and put it into action,” said Patnode.

With the help of Lieutenant John Corbett, a retired 42 year veteran of the Syracuse Police Department, Patnode, who also spent 20 years on the force, created a “drug deal gone bad” scenario, an awkward characterization used regularly in the media. Evidence was placed in a classroom and nearby bathroom in Mawhinney Hall which could lead students playing the role of investigators to conclude someone had been stabbed and robbed during an attempted drug transaction in a classroom. In the classroom there would be overturned desks, a bag with drugs in it, a bloody knife, and a trail of blood which led to a bathroom next to the classroom.

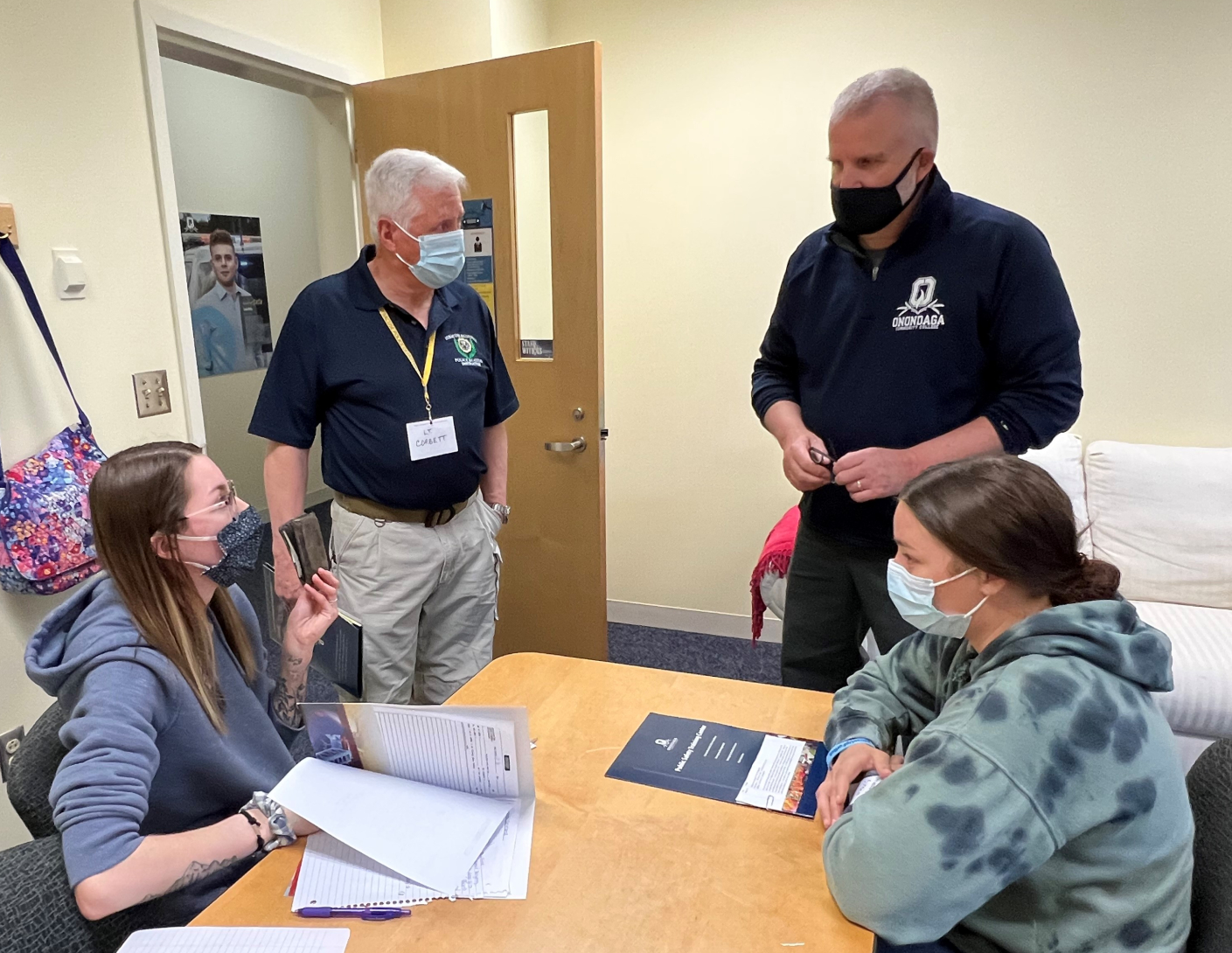

Students were assigned specific roles including patrol officer, crime scene evidence recorder and collector, detective, 911 caller, victim, and suspect. They learned their roles just before the exercise began, and students were not informed of what each was doing. They would have to figure it out as the crime was unfolding.

The scenario began with a student making an emergency 911 call, informing first responders of a disturbance and what he had observed. Student Gage Simmons was the first responding officer and had to secure the area, putting up police tape to block access to the hallway which led to a classroom and bathroom where there was evidence. "Doing that for the first time was a little jarring. It was very hectic. I had to keep my eyes all over the place and control the scene because you don't want the scene contaminated," said Simmons.

After the scene was secured three students wearing white disposable suits began collecting evidence and taking pictures. Based on the evidence, the disturbance was quickly upgraded to a stabbing and a robbery. At the same time, student detective Miranda Cleveland was interviewing the 911 caller and the suspect. When she asked the suspect to empty her pockets, she found the victim's wallet which sealed the case. "Going through this helped me know what to expect if I'm going to be a detective one day. I learned I have a lot of work in my future getting statements and filling out paperwork," Cleveland said.

While the exercise had some bumps along the way, it produced the result Professor Patnode was hoping for. "They got a face full of the chaos at the initial onset of a crime scene. It's all controlled in a textbook. The end piece about 'holy cow look at all this paperwork' is really important. You can be the best detective in the world. If you can't put it on paper like it happened, it's not going to go anywhere. I liked the engagement. They were all engaged."

Lieutenant Corbett, who spent decades solving crimes and training new officers, also thought the exercise provided students with a great experience. "Visual learning is the most valuable. You can read books, but to get out and do things or see how they're done, that's the way to go."